It is time to cover the entire cycle of waste generation, collection and dumping, and also question excessive consumerism by the affluent.

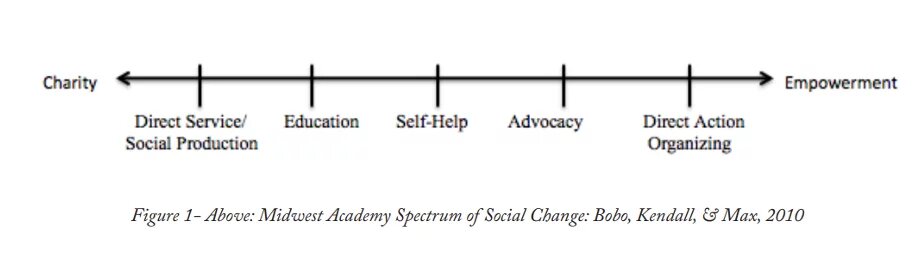

Clean-up drives have become one of the most important and common community actions people take to address growing environmental concerns in India. Millions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds are being diverted towards the beautification and cleanliness of parks, beaches and roads every year. Even though clean-up drives are projected as a one-stop saviour for our excessive waste issue in cities, bringing about social change requires a range of actions, such as social service, self-help, education, advocacy and direct action as laid out by Kim Bobo, Jackie Kendall and Steve Max in 2010:

Clean-ups are, simply put, a ‘direct service’, a short-term fix that makes a specific place look clean and hygienic for a while until the next time people come and litter. In fact, people who have been a part of clean-up drives have themselves sometimes questioned the efficacy of such activities. Some groups conduct bi-monthly or weekly clean-ups in the same spot. The volunteers often find the same amount of waste the next time they come after a clean-up and find it disheartening. Posing clean-up drives as the solution to our environmental issues, specifically the burgeoning waste problem in urban spaces is problematic on various fronts. One, it does not address the source of the problem: The growing middle class and an entrenched elite class, which produce the majority of the waste. Consumer culture, which is widely prevalent in the middle and upper classes, likewise remains unchallenged. Second, through these clean-ups, we also do not question the end location and destination of such waste. Once the clean-up has finished for a day, and all the big bags full of mixed waste are collected, they must be dumped somewhere. That ‘somewhere’ is usually the landfills where all other waste of the city goes. The waste still remains unprocessed, unsegregated and piling up in landfills. This means that through these clean-up drives, we are simply changing the location of the problem, usually from an area frequented by middle class people to a landfill. Third, and as is evident in the spectrum of social change, power relations are not questioned through this approach. Consumerism is not questioned, and the demand for such material plenty by middle and upper classes is not questioned. Fourth, There is an entire value chain related to waste, waste pickers, recyclers and sweepers whose rights, concerns and role in keeping the city running is never taken into account. The waste ends up in landfills where these poorly paid waste workers who work and usually live near the landfills in unhygienic and unsafe conditions, pick, segregate and recycle our waste while the remaining waste keeps piling up and the height of the landfill keeps increasing. Therefore, it does not solve any of these long-term issues.

By-product of capitalist society

Production, consumption and the waste it creates are all tied up to the idea of the impact of capitalism on our society and the environment. Alan Schneiberg in his book “The Environment: From Surplus to Scarcity” draws a relationship between capitalism, the state and the environment. He says that "our environmental problems are a natural by-product of the structure of an industrialised capitalist society, which is a treadmill of production". This kind of an economic system continues to pursue and yield profits by creating consumer demand for new products, even if this expanding consumer demand leads to the exploitation of the environment beyond its limits or carrying capacity. The creation of consumer demand is fueled by constant advertising of products for practical usage or lifestyle enhancement. This kind of advertising is today rampant on all social media platforms that we use, including traditional modes of mass media such as television, radio, and newspapers.

Clean-up drives mostly do not lead to a reflection among participants about the source of the waste that is around them. It does not question in the least bit, the system, which constantly pushes people to buy and throw away new objects. Clean-up drive participants usually consist of urban middle and upper class citizens, who are the primary consumers in Indian markets. While the definition and therefore the population of the middle class in India is disputed, it is largely agreed that the middle class is fast expanding in India. With the growth of the middle class, there’s an expansion in consumer demand, especially fast-moving consumer goods, cosmetics, beverages, processed and packaged food items such as chips, chocolates, sauces and snacks. The most visible aspect of the growth of the new middle classes in developing economies has been the rise of brand consciousness, shopping malls and advertising. The rise of the middle class, growing disposable income, and expansion of consumerism are different sides of the same process.

In his essay “Consumerism and the Indian Middle Class”, Ashish Kothari says that there are many reasons to interrogate consumerism in India and worldwide. (Kothari 2017). The most important one is that it leads to the exploitation of ecosystem services to a point of no return. To keep consumerism in check, he provides an interesting suggestion – the introduction of a sustainable consumption line; it would help governments determine whether an individual or family is living sustainably and consuming resources within certain mandated limits. A sustainable consumption line can be implemented in energy consumption, water usage, transport and most importantly, in this context, waste. And, he suggests having “sustainable waste”, where every household would be allowed to generate only a certain amount of waste, beyond which it would have to be recycled, composted or otherwise dealt with within the premises of the community/ colony. He further discusses the adoption of the sustainable consumption line by the middle classes and says that a substantial section of environmental civil society organisations is led by the middle class. They are often oblivious to the systemic marginalisation of minorities and the social justice aspects of environmental issues (Kothari 2017). They, at times, end up advocating for policies, which cause further marginalisation among disadvantaged groups while some restrict themselves to reformist and superficial solutions. As long as middle-class civil society organisations keep using clean-up drives as an avenue for their communities to absolve themselves of the responsibility and guilt of generating huge amounts of waste, an alternative vision and system of managing our waste will never emerge.

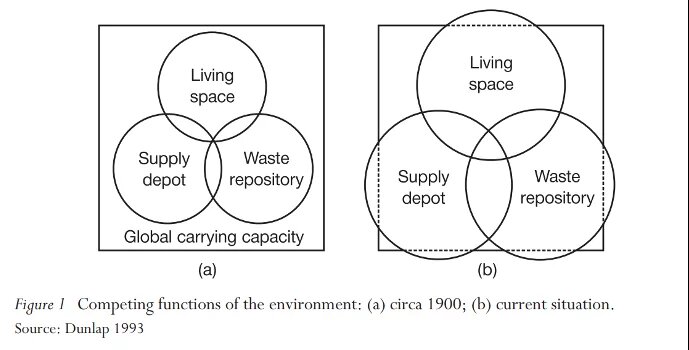

The burgeoning waste problem has also come to the notice of middle-class citizens in the recent decade because of competing functions of the environment around them becoming more acute. Sociologists William R. Catton, Jr. and Riley E.Dunlap have suggested a model for understanding ecological destruction, where they specify the “three general functions the environment serves for human beings: supply depot, living space and waste repository”. The supply depot function denotes all the natural renewable, and non-renewable supplies we get from the environment around us such as food, timber, oxygen, temperature regulation, and fossil fuels for our daily needs. As a provider of living space, we use land to build housing projects and transportation systems. Lastly, with the waste repository function, the environment serves as a ‘sink’ for garbage, sewage, industrial pollution and other byproducts. Each of these functions competes for space and impinges on each other. (Gould, Pellow and Schnaiberg 2004). The Ridge area in New Delhi is a classic example where there is a conflict between the three functions it serves. First, increasing migration to Delhi in post-Independence era led to several housing projects erupting on the Ridge land. Almost simultaneously waste came to be dumped in different patches of the forest, and turned it into wasteland. However, the Ridge also serves as a supply depot because it contributes significantly to the regulation of temperatures and water in the city. Many people living on its fringes also derive fuel wood from it. Thus, in recent years, the overlap, and therefore conflict, among these three competing functions of the environment has grown considerably, leading to stronger sentiments around the waste issue. All three of these functions of the environment have pushed the limits of the adaptive capacity of the environment beyond its carrying capacity.

Fixing entire cycle

Young people need to realise the need to move beyond surface-level solutions such as clean-up drives. While cleaning up certain areas is a service, and it helps temporarily fix the waste issue in our neighbourhoods, there is a need to engage in advocacy and watchdog functions as active citizens. Clean-up drives can be used to initially mobilise people, educate them and raise their consciousness regarding the waste that they generate. However, it has to be followed by organising people towards the goal of fixing the entire cycle of waste generation, collection and dumping. As laid out by the Spectrum of Social Change by Bobo, Kendall and Max, we have to move from service, towards education, to self-help, then advocacy and finally direct action organising.

There are authorities who can be approached (usually municipality) and held accountable if waste is not being segregated, collected or recycled as mandated by the Solid Waste Management Rules. Advocacy by organising and mobilising citizens to pressurise the local governments to carry out their responsibility of managing waste sustainably is a path that can achieve long-term solutions. Advocacy should also include the incorporation of informal recyclers, collectors, waste workers and scrap dealers in the waste value chain, by securing their rights. They have always played an instrumental role in the waste management system of our cities, but the privatisation of these services is leading to their exclusion and unemployment. Finally, striving to shift consumer patterns, in the long run, is also an essential aspect of working in this sector. Reducing our consumption, refusing to buy excessive things and reusing items in our household has the least amount of carbon footprint, thereby being our most favourable path going forward.

References

Gould, Kenneth A., David N. Pellow, and Allan Schnaiberg.2004. “Interrogating the Treadmill of Production: Everything you wanted to know about the Treadmill but were afraid to Ask.” Organization and Environment 17 (3).

Kothari, Ashish. 2017. “Consumerism and the Indian Middle Classes.” In The New Middle Class in India and Brazil: Green Perspectives?.N.p.: Academic Foundation, Heinrich Böll Stiftung

Lahiri, Ashok K. 2017. “Green Politics and the Indian Middle Class.” In The New Middle Class in India and Brazil: Green Perspectives?.N.p.: Academic Foundation.

Santosh, Sidharth, and Oliver Harman. 2020. “Tendering trash: Lessons in urban waste management from Indian cities - IGC.” International Growth Centre. https://www.theigc.org/blog/tendering-trash-lessons-in-urban-waste-mana….